Deploying to all the clouds with Serverless Framework

In my last post, I described how my colleague Ian Cole and I implemented some web scraping code to wrangle aircraft photos into Tableau. One possible approach was a serverless function (i.e. a snippet of cloud-hosted code that executes on-demand) to retrieve a photo of a particular aircraft in response to a click on the Tableau viz. In the end, I opted to pre-fetch the photo URLs using a batch process, but I gained some useful experience building and deploying serverless functions to different cloud platforms. This post digs into how this was done using the Serverless Framework.

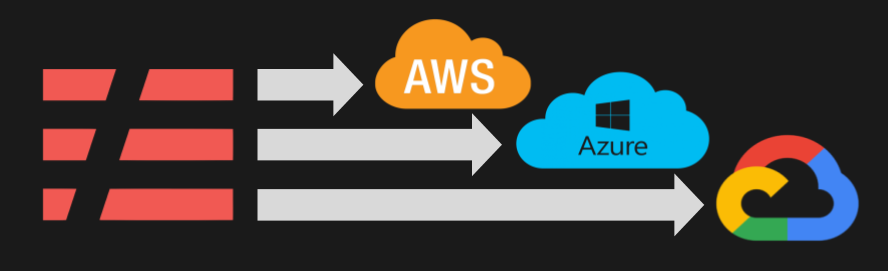

The Serverless Framework is an open-source project introduced in 2015 that’s designed to automate some of the grunt work of deploying serverless functions. It originally targeted only AWS Lambda but has since grown to support other “Function as a Service” providers such as Azure and Google Cloud, as well as IBM/Apache OpenWhisk, Oracle Fn, Kubeless, SpotInst and Cloudflare. It seeks to provide a platform-agnostic interface into the parts of these platforms that are functionally equivalent (so to speak) but are defined using different formats. By making functions more portable, it helps address one of the biggest concerns organizations face when building in the cloud: How to avoid “platform lock-in” — i.e. being too dependent on one platform, and thus vulnerable to its pricing and availability constraints.

(Of course, you might ask whether this is just moving your dependency to another player, and a less known/established one at that. Fair point. The framework is maintained by Serverless Inc., a privately held, investor-backed company. However, it is open-sourced under the MIT license, has a healthy community of contributors, and doesn’t do any magic beyond translating your configuration into the target platform’s resource management format.)

The Serverless Framework also encourages the best practice of defining infrastructure as code. All the cloud platforms provide user interfaces for setting up services, but defining them in configuration files makes your setup far more reproducible, testable and shareable. There are other, more generic frameworks for achieving this, such as Ansible, but your situation may or may not be best served by a Swiss Army knife solution.

So when we set out to try the serverless approach to aircraft photo scraping, it made sense to try to Serverless Framework and see if it lives up to its aspiration of making the process easier. we found that it was easy but not effortless. Below are the main steps we followed to deploy to AWS, Azure and Google Cloud, as well as some gotchas we encountered.

Getting Started

The Serverless Framework uses Node.js, so even if your function is not written in Node.js, you will need to install it, then npm install -g serverless. The framework supports AWS out of the box, but if you’re deploying to Azure or Google, you’ll need to npm install the appropriate plugin. Then you can run npm create --template {platform and language you’re using} --path {what you want to call it} to generate scaffolding to get you started.

Account Setup

With all three services, you’ll need to set up an account and install local credentials to give the framework permission to deploy code on your behalf. This is inherently platform-specific but well documented for each platform in the Serverless Getting Started Docs.

If you don’t already have an account, all three offer generous free tiers and trial periods. AWS and Azure give you 1 million free requests per month. Google gives you 2 million. In addition, Azure gives you a $200 credit to spend on any services, but it expires after 30 days. Google gives you a $300 credit that lasts 12 months. AWS doesn’t have a trial credit, but many of its other services have free tiers that you can use to try them out.

One other pricing difference to note: While all three offer the requisite on-demand pricing model based on number of requests and compute time, Azure also offers fixed “App Service” pricing if you want to provision your function on an alway-on virtual machine.

Serverless.yml

The heart of the Serverless Framework is the serverless.yml config file, which is generated when you run serverless create. For a basic function, the serverless.yml configs are remarkably compact and similar across platforms:

AWS:

service: my-unique-service-name

provider:

name: aws

runtime: nodejs8.10

functions:

my-function-name:

handler: handler.my-js-func-name

Azure

service: my-unique-service-name

provider:

name: azure

location: West US

plugins:

- serverless-azure-functions

functions:

my-function-name:

handler: handler.my-js-func-name

events:

- http: true

x-azure-settings:

authLevel : anonymous

- http: true

x-azure-settings:

direction: out

name: res

Google:

service: my-unique-service-name # NOTE: Don't put the word "google" in here

provider:

name: google

runtime: nodejs

project: my-project-id

credentials: ~/.gcloud/keyfile.json

plugins:

- serverless-google-cloudfunctions

functions:

my-function-name:

handler: my-js-func-name

events:

- http: path # the value of this key is ignored. It is the presence of the http key that matters to serverless.

A couple of quirks to point out about the Google version:

- Google oddly requires that you include

http: {some value}in your serverless.yml, though the value is ignored. - It exposes the local location of your credentials file. Not sure how much of a concern that is, but it gave me pause.

These are just the bare-bones required settings. Many other options can be specified if you want to vary from defaults.

Function Portability

In addition to platform-specific differences in the serverless.yml, your function itself needs to be tailored somewhat to the specific platform. All three platforms support Node.js functions, but their method signatures, logging and response formats are slightly different:

AWS handler.js:

'use strict';

module.exports.my-js-func-name = async (event, context) => {

console.log('JavaScript HTTP trigger function processed a request.');

return {

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify({

message: 'Hello World!',

input: event,

}),

};

Azure handler.js:

'use strict';

module.exports.my-js-func-name = (context) => {

context.log('JavaScript HTTP trigger function processed a request.');

context.res = {

// status: 200, /* Defaults to 200 */

body: 'Hello World!',

};

context.done();

};

Google index.js:

'use strict';

exports.my-js-func-name = (request, response) => {

console.log('JavaScript HTTP trigger function processed a request.');

response.status(200).send('Hello World!');

};

A couple of differences to pay attention to:

- The convention for AWS and Azure is to put your functions in

handler.js. Google, on the other hand, assumes that you are naming your fileindex.jsorfunction.js, though you can override this by specifying a different main entry point in yourpackage.json. - AWS and Google use

console.logfor logging, whereas Azure usescontext.log.

Our web scraping function was pretty generic and didn’t rely on any other cloud services, like databases, file storage or message queues. So I expected it to be pretty portable across platforms. It was initially written for AWS Lambda, so porting it to Azure required a minor rewrite. Porting to Google Cloud required yet another. I had already refactored the core retriever logic out of the handler function, but now I had three different versions of the handler, including repeated error handling code. I refactored this one more time to keep the absolute minimum in the platform-specific handlers:

'use strict'

const path = require('path')

const retriever = require(path.join(__dirname, '//retriever.js'))

module.exports.getjetphoto_aws = async (event, context) => {

let tailNum

if (event.tailNum || event.queryStringParameters.tailNum || JSON.parse(event.body).tailNum) {

tailNum = (event.tailNum || event.queryStringParameters.tailNum || JSON.parse(event.body).tailNum)

}

let response = await getjetphoto(tailNum)

console.log(response.log)

return {

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'text/html' },

statusCode: response.status,

body: response.body

}

}

module.exports.getjetphoto_azure = async (context, req) => {

let tailNum

if (req.query.tailNum || req.body.tailNum) {

tailNum = (req.query.tailNum || req.body.tailNum)

}

let response = await getjetphoto(tailNum)

context.log(response.log)

context.res

.type('text/html')

.status(response.status)

.send(response.body)

}

exports.getjetphoto_google = async (req, res) => {

let tailNum

if (req.query.tailNum || req.body.tailNum) {

tailNum = (req.query.tailNum || req.body.tailNum)

}

let response = await getjetphoto(tailNum)

console.log(response.log)

res

.type('text/html')

.status(response.status)

.send(response.body)

}

async function getjetphoto (tailNum) {

let response = {}

if (tailNum) {

const result = await retriever.getjetphotos(tailNum)

if (!Array.isArray(result)) {

response.log = `Retriever error ${result}`

response.status = +result.match(/\[(\d+)\]/)[1] || 400

response.body = result

} else if (result.length === 0) {

response.log = 'No photos :-('

response.status = 204

response.body = wrapHtml('No photos :-(')

} else {

response.log = `Retrieved ${result.length} photo URLs`

response.status = 200

response.body = wrapHtml(imgTag(result[0]))

}

} else {

response.log = 'No tailNum'

response.status = 400

response.body = 'Please pass a tail number on the query string or in the request body'

}

return response

}

function imgTag (photo) {

let html = `

<figure>

<img style="max-width: 500px;" src="https:${photo.photo_url}" alt="">

<figcaption>Photo by ${photo.photog}</figcaption>

</figure>`

return html

}

function wrapHtml (content) {

return `<html><body>${content}</body></html>`

}

Dependencies on other common cloud services like file storage could be handled in a similar fashion. However, relying on any very platform-specific features (like some of the amazing new machine learning services) will limit the portability of your code.

Testing

The Serverless CLI allows you to serverless invoke local your function as long as there are no dependencies on other online resources — i.e. it does not provide local mocks for any other cloud services that your function might be calling. But isolating and mocking such dependencies should be part of your automated test coverage. Refactoring the core photo retrieval logic out of the handler module made it easier to write test cases using mocha and chai, and mock dependencies with sinon, moxios and mock-fs.

Deploy

Once you’re ready to deploy your function, running serverless deploy takes care of generating all the platform-specific resources and pushing your code to the cloud. You can inspect all the resulting AWS CloudFormation, Google Resource Manager or Azure Kudu deployment assets in the invisible .serverless directory or your function’s root directory.

However, I encountered one major gotcha when trying to deploy the same function on multiple providers: Each provider requires a separate serverless.yml file, and there is currently no way to specify a different file when you run serverless deploy. (I contributed to a pull request to add this as a CLI option, but as of this writing it is not merged.) As a workaround, you can create separate config files named serverless-aws.yml, serverless-azure.yml, etc., and use a simple bash script to swap config files when you deploy:

#!/bin/bash

if [ "$1" != "" ]; then

echo "copying serverless-$1.yml to serverless.yml and running serverless deploy"

cp serverless-$1.yml serverless.yml && sls deploy

else

echo "Please append provider, like 'deploy.sh aws' or 'deploy.sh azure'"

fi

I also encountered an annoying tendency of Azure not to update all files when redeploying a function, leading to confusing errors until I discovered the old code in the Azure console, deleted the function, then deployed a fresh copy.

Performance Differences

Once I adapted the JS code to suit each service and deployed it, they all “functioned” as expected. But I did notice some performance differences, particularly that Azure had a much slower deployment and cold start performance.

| Platform | Deploy Time | Cold Start Run | Warm Start Run |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWS | 1m 40-50s | 2.1-2.8s | 0.8-1.3s |

| Azure | 6-7m | 1-2m | 0.7-1.7s |

| 2m 40-50s | 2.6-2.7s | 1.0-1.7s |

Note these are unscientific measurements. I have not tried to exhaustively benchmark the services under controlled conditions.

A few other details

Two other minor things to note:

- Serverless does not pay attention to your

.gitignorefile. Every file in your directory will get deployed unless you add exclude rules to yourserverless.yml - Each service exposes different names in the function console and URL. For example, AWS and Azure URLs use the function name defined in your

serverless.yml, whereas Google uses the JS function name:

AWS URL structure:

https://{some-aws-id}.execute-api.{region}.amazonaws.com/prod/{my-func-name}

Azure URL structure:

https://{my-unique-service-name}.azurewebsites.net/api/{my-func-name}

Google URL structure:

https://{region}-{my-project-id}.cloudfunctions.net/{my-js-func-name}So pay close attention to how you name things and what you want publicly visible.

Conclusion

All in all, I found the Serverless Framework to be an easy on-ramp for trying out different cloud providers. The experience also spurred me to write more platform-independent code, which is always a good thing. All of these platforms are evolving fast, so it behooves you to trying them out, use design patterns that can translate across platforms, and avoid platform lock in.

.jpeg)